As the world grapples with the fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic, the international trade system is being buffeted by demand shocks, trade restrictions, and supply chain disruptions. The global pandemic will have profound and lasting effects on global trade, many of which are impossible to predict. Among early developments, we see a wave of countries and regions, including China, EU, U.S., and Japan, reverting back to protectionist policies for medical equipment and other products, and the prognosis for how the current situation impacts the clean energy transition remains speculative for now. As the world slowly recalibrates its trade policy and industry recalibrates its supply chains, philanthropy must remain watchful for windows of opportunity to shape these changes and drive positive outcomes for the climate. Drawing on our contribution, “Trading Blame or Exporting Ambition?,” to the recent Overseas Development Institute publication titled “Counting Carbon in Global Trade,” we highlight here why trade matters for the climate, how its impact on emissions can be tracked, and what philanthropy can and should do in response.

Why trade matters for climate: Friend and foe

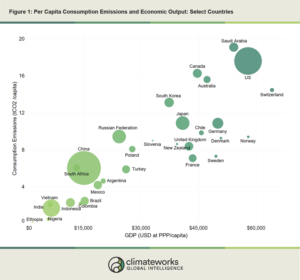

Trade is a tool that can be leveraged for climate action, but the current reality is decidedly more mixed. Trade enables economic activity that contributes to rising greenhouse gas emissions, and the sheer volume of traded goods and services, as well as the varied policy regimes they are subject to, offer both the potential for clean procurement and a liability for carbon leakage, in which the production of carbon-intensive goods shifts to jurisdictions with lax environmental standards. In some cases, national laws put a higher price on emissions produced in-country, leading to carbon leakage by driving substitution toward imported goods or services that can be provided more cheaply without adherence to these standards.

Following trade emissions

How can philanthropy help

Philanthropic resources deployed for the public good have the power to catalyze action and accelerate climate solutions. Given the global reach of international trade, there is a need to assess how and where to advocate for policies that help realize trade’s potential for driving decarbonization.

It is unclear the extent to which Covid-19 will reshape the world and economies in the next few years, especially in relation to trade. As part of the economic recovery process, we expect to see increased infrastructure investments as part of many fiscal stimulus plans that are being enacted around the world, as well as the need to shorten and nationalize supply chains. These can have a large impact on consumption, tariffs, trade barriers, labor markets, trade flows and agreements, new alliances in response to protectionism, and other outcomes. There are many such trends to watch for, as well as new opportunities to influence low-carbon investments. We list a few examples in Table 1.

The way forward

The global trade system is at an inflection point, buffeted by the U.S.-China trade war and the physical and economic shock of the Covid-19 pandemic. This is an opportune moment to step back and reflect on what outcomes the current system is driving, and to reimagine how trade can be put to work for climate change mitigation. Public procurement and environmental standards, climate clubs, and border carbon adjustments are all different means to the same end — to stimulate green investments, prevent carbon leakage, and to harness the skills and resources of the global community to tackle this pressing global challenge.