Guest blog by partners from the Institute for Essential Services Reform

As host of the recent G20 conference, Indonesia plays an increasingly prominent role in the global energy transition. During the summit, there were numerous notable policy achievements and commitments. However, questions still remain, particularly regarding implementation plans to phase out coal and deploy renewable energy for the nation. We are delighted to invite our partners from the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR) in Indonesia to share their takeaways from the G20 summit and the implications for renewable investments, most importantly solar, in the years to come.

In November, Indonesia concluded its G20 presidency, reaching several milestones toward a clean energy transition. These include the Bali Compact (G20 Energy Ministers’ agreement), the announcement of Indonesia’s Energy Transition Mechanism (ETM) Country Platform, and the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) — a commitment to mobilise USD 20 billion in public and private capital to peak power sector emissions by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050. Under the JETP, Indonesia will prepare an investment plan in the six months following the announcement.

These outcomes are the culmination of a series of intentions made since last year. In 2021, President Joko Widodo announced a 2060 net-zero emissions target and ordered PLN (the powerful Indonesian energy utility) to stop building new coal plants beyond the project agreed upon in the 2021-2030 Electricity Development Business Plan. At COP26, Indonesia also agreed to the Global Coal to Clean Power Transition, which contains a pledge to transition away from unabated coal power generation by the 2040s or sooner.

Setting the stage

In 2014, the country set a target to achieve a 23 percent renewable energy mix by 2025. Since then, the government has attempted to drive more renewable energy by providing policy support and incentives to different sources. It has a weakness, as the policy is only driven by energy-related ministries, cross-cutting issues and necessary measures to ensure they are implemented properly are simply not there.

Prior to 2022, Indonesia was sending mixed signals on the coal phase-out. Coal production is always historically higher than government target limits, and PLN’s electricity business plan still accommodates plenty of new coal power plants. In September 2022, the president finally signed a groundbreaking regulation administering the early retirement of coal power plants and a moratorium for new coal power plants after 2030. Coupled with the financing mobilisation effort announced at the G20 Summit, Indonesia is ready to go beyond the high-level event and pave the way for the energy transition.

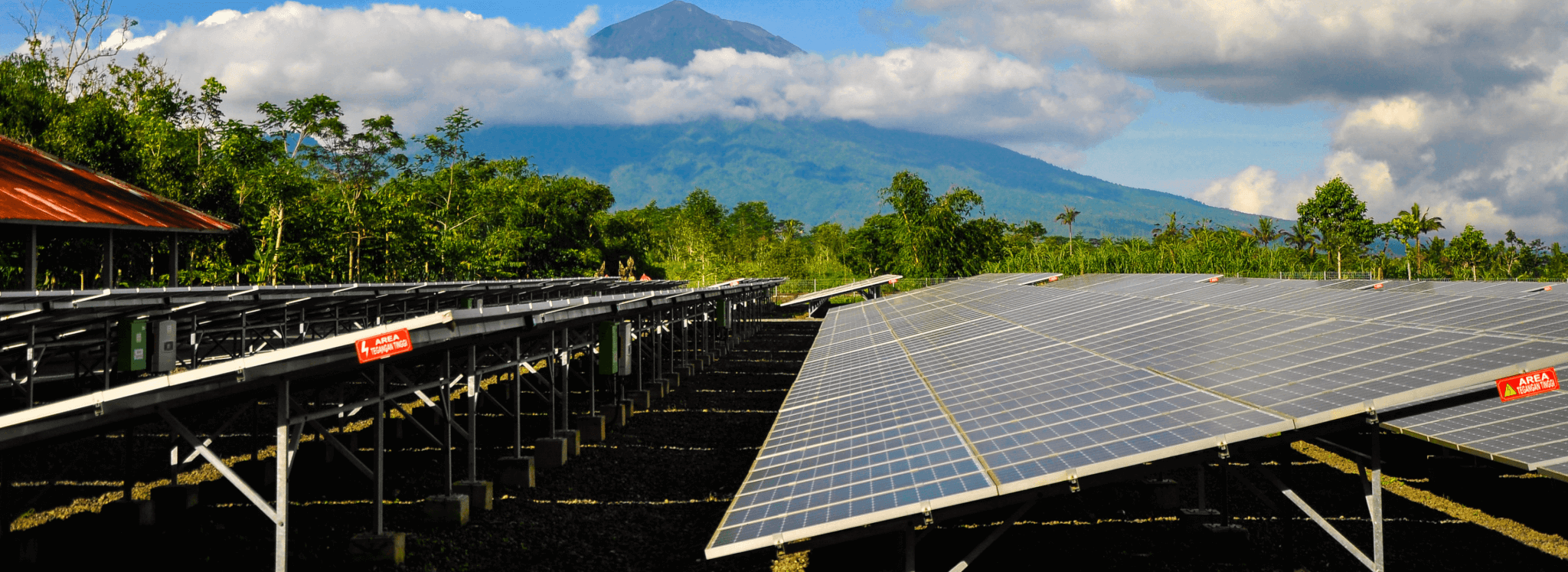

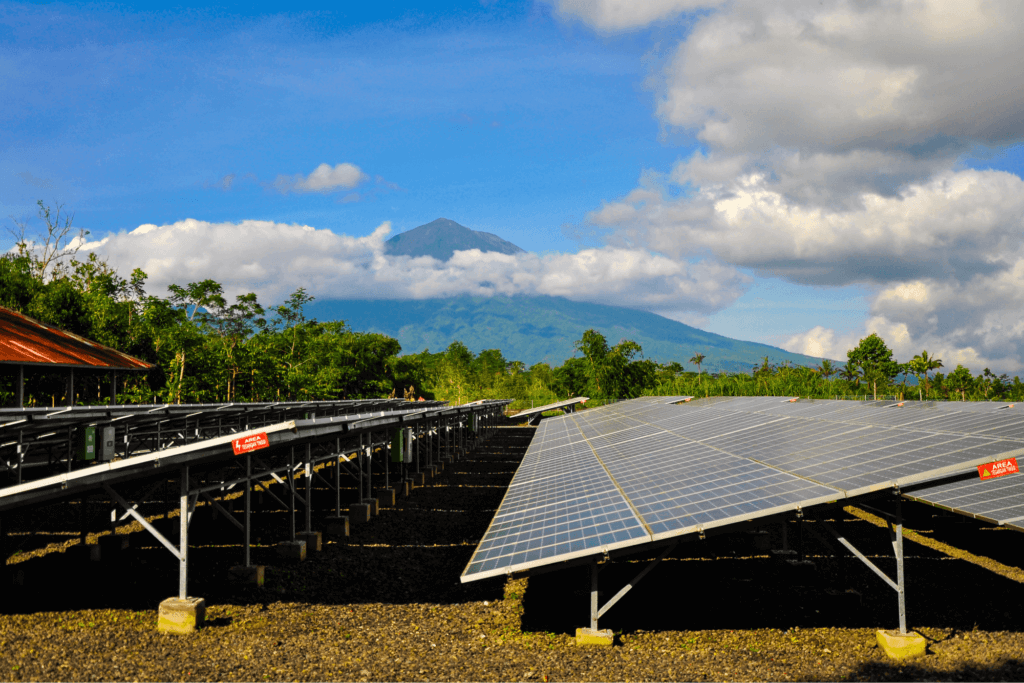

The presidential regulation (No. 112/2022) is particularly important in three key areas: coal phase-out is on the table, cross-ministries cooperation is mandatory, and there are better renewable energy tariffs. Both the ETM country platform and JETP attempt to accelerate coal overcapacity and the existing coal fleet’s early retirement, which will carve room for more renewables in Indonesia’s energy system — including solar. In fact, the solar energy potential in the country is up to 20,000 GWp, according to estimates by IESR. Solar energy has made its way into Indonesia’s decarbonization pathways for net-zero emissions by mid-century. However, mobilising finance and investment for solar is a daunting task. IESR has calculated that USD 32.9 billion by 2030 is needed for solar alone to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.

(Fun fact: the authors of this blog both have rooftop solar installed on our homes in Indonesia)

Solar energy entered Indonesia’s mainstream policy and discourse in 2018 when the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources issued the inaugural regulation (MEMR Reg. No. 49/2018) for rooftop solar. Two years prior, we at IESR started advocacy work on solar energy with the strategic aim of making solar policy a priority and opening the door for other renewables. With several solar champions, we established the Indonesia Solar Energy Association and later worked on the one million rooftop solar national movement (GNSSA). Since the issuance of this regulation, rooftop solar ultimately grew in a more substantial way in Indonesia, with an annual average growth of 1,300 users and 15 MWp cumulative installations. Revisions made in 2019 that decreased parallel charge for industrial consumers, coupled with the availability of a solar leasing scheme, further boosted adoption in the segment. In 2022, we saw 2018’s ministerial regulation on rooftop solar PV being replaced with a better one (MEMR Reg. 26/2021). Unfortunately, however, the regulation is only effective on paper. Different PLN regional branches have imposed a nationwide capacity limitation, including rules that users can only have 10% to 15% (sometimes lower) of their existing power installation come from rooftop solar. This severely discourages new users and makes the economic benefits of rooftop solar unattractive.

Looking forward

We believe that solar will remain a key renewable energy source for Indonesia’s decarbonization efforts. There is a solar project pipeline of 2.3 GW until 2023 that we have collected from the Indonesia Solar Summit 2022 in April, hosted by MEMR and co-hosted by IESR with support from Bloomberg Philanthropies. However, those projects are delayed and at risk of not being completed due to capacity limitations, which also puts a strategic national program of 3.6 GW rooftop solar at bay. Out of frustration, six foreign chambers of commerce (British Chamber of Commerce, European Chamber of Commerce, Japanese Chamber of Commerce, Korean Chamber of Commerce, Swiss Chamber of Commerce, and U.S. Chamber of Commerce) also sent out a joint letter addressed to President Jokowi in September, asking him to take charge and lift the hurdles to rooftop solar installation, particularly for the commercial and industrial segments. In it, they also asked that limitations be imposed at the system level, not per customer. It is recommended that the government put concentrated measures to solve this problem immediately, as there are only three effective years left to meet the renewable energy target and rooftop solar is the quickest fix.

The newly released Indonesia Solar Energy Outlook 2023 highlights floating solar’s role in driving utility solar development in Indonesia. Traditionally, allowing variable renewable energy (wind and solar) into Indonesia’s power system is often met with resistance due to overcapacity issues, scattered auctions, and site selections. The last utility solar tender held was in 2019 for two 25 MWp solar projects in Bali — its PPA was only signed in Q1 2022. As of Q3 2022, there are three floating solar projects totaling 255 MWp under development: one through G2G cooperation (Cirata 145 MWac) and two under PLN’s subsidiary equity partner auction (Singkarak 50 MWac and Saguling 60 MWac). Their bid price has set a record 85% price decrease from 2015. A full IPP scheme of multiyear, transparent auctions should be conducted to provide clear indications to investors and increase competition to get the best price and quality.

It is also pertinent to ensure the social and economic benefits of the energy transition. Only four provinces in Indonesia are responsible for nearly 90% of Indonesia’s coal production, making the people who work there vulnerable to loss of jobs and livelihoods as we transition into renewable energy. An economic transformation requires careful planning and years if not decades of preparation. Key planning aspects include the identification of transition impacts, alternative economic sectors, employment transfers, and social safety nets. With more solar projects coming, and with the potential for better policy support and implementation, solar industries could provide a central option for this transitioning workforce.