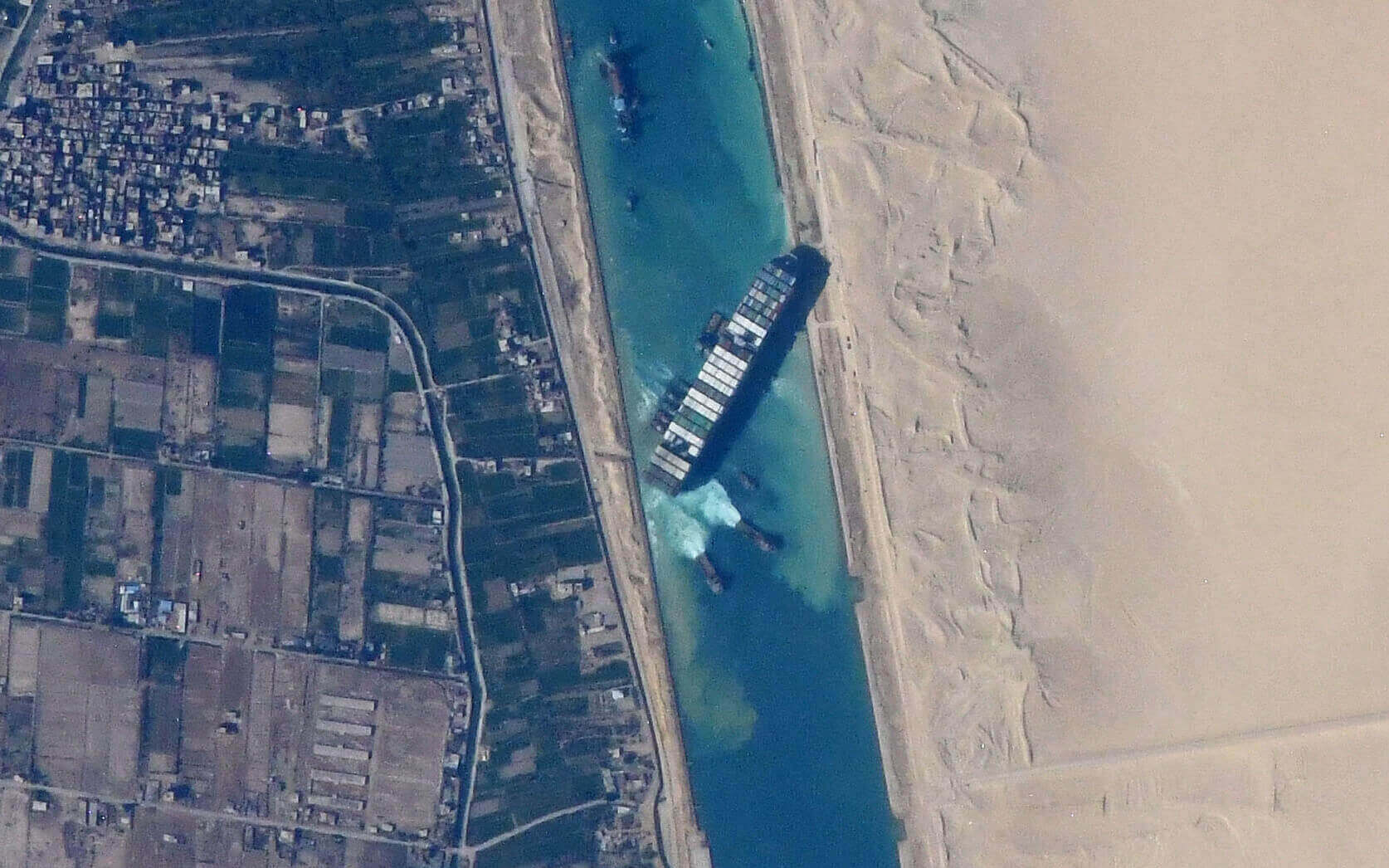

In March of 2021, a ship the size of the Empire State Building called Ever Given got stuck in the Suez Canal, crippling global trade to the tune of $10 billion a day and inundating social media with memes poking fun at the pathetically wedged-in vessel. The incident added to the supply-chain woes of the coronavirus pandemic, when consumers around the world seemed to realize for the first time that the boxes landing on their doorsteps had arrived there thanks largely to journeys by sea. And yet for all the attention recently enjoyed (or suffered) by maritime shipping, the sector’s real news — a fast-moving decarbonization movement — was playing out behind the scenes.

The general public may finally know something about cargo ships and containers, but few may realize the extent to which the multi-trillion-dollar shipping industry pollutes our planet. The sector is responsible for 3% of global greenhouse gas emissions — as much as aviation — and its emissions could double by 2050. Ships run mainly on the thick sludge that remains at the end of the oil-refining process, and if we are to limit the increase in global temperatures to 1.5° C, we will need to transition to energy sources with much lower carbon footprints. That will mean figuring out what those sources are — green ammonia and green methanol are the leading contenders — and then overhauling our ships and building new port infrastructure to support them.

Unfortunately, the industry’s unique character — with activities taking place mostly on the high seas so no single country takes responsibility, and owners registering vessels in whichever jurisdiction promises the least expense and oversight — has made it harder for countries to take meaningful action on their own. And efforts to cut emissions through international regulations have been routinely met with resistance from shippers and oil companies. The International Maritime Organization (IMO), the U.N. agency that regulates international shipping, has announced a goal to at least halve ship emissions by 2050, but that target would be both too little and too late.

At ClimateWorks Foundation, we know that there isn’t time to waste. Our grantees are working with partners all along the value chain — from port operators, ship owners, and carrier companies to the consumer-facing brands that rely on shipping — to decarbonize everything, fast. Many of the solutions needed to transform international maritime shipping into a zero-emissions industry by 2050 aren’t yet on the water, but we’re collaborating with civil society organizations, portside communities, and the private sector to reshape the commercial and policy environments to accommodate them when they arrive.

Among the most promising initiatives we’re supporting are green shipping corridors. In 2021, at the COP26 meeting in Glasgow, the U.K. government announced the launch of the Clydebank Declaration for green shipping corridors. These are routes between two major port hubs in which the technological, economic, and regulatory conditions are in place to support the operation of zero-emission ships. Signed by 24 governments, the Declaration, which pledges to establish half a dozen such routes by 2025, is meant to cut through the complexity involved in decarbonizing shipping. The goal is to inspire actors, both public and private, to make early-mover commitments and take on projects that jumpstart a sector-wide transition and move the industry toward its goal of a tipping point of 5% green fuels by 2030.

In addition to providing a way for local, state, and national governments to move forward independent of the IMO, the corridors help address a chicken-and-egg problem that’s currently holding transition efforts back. Ship and port owners are reluctant to invest in vessels and bunkering facilities that use expensive alternative fuels until they know which ones are likely to be adopted — and that they’ll be available where needed. But only widespread adoption by those very actors will achieve the economies of scale necessary for the fuels’ prices to fall. Our partners at theAspen Institute have put together a network, Cargo Owners for Zero Emission Vessels (coZEV), of major freight customers such as Amazon and IKEA who are stepping up their commitments as a way of indicating to shipping leaders like Maersk that demand for green-shipping is emerging and that they should begin shifting their fleets toward cleaner vessels. “In the end,” says the Institute’s Ingrid Irigoyen, “it’s about the money. Can you afford to make the transition?”

“Ports have become some of the most acute centers of fossil-fuel pollution on the planet. You have ships, trucks, trains, planes, and all these goods and personnel moving through, and almost all of it is run by fossil fuels.”

— Madeline Rose, Pacific Environment

But going green isn’t just about climate change. As Madeline Rose, the campaign climate director for our partner Pacific Environment, points out, “Ports have become some of the most acute centers of fossil-fuel pollution on the planet. You have ships, trucks, trains, planes, and all these goods and personnel moving through, and almost all of it is run by fossil fuels.” Most ports remain overwhelmingly powered by diesel, a fuel that disproportionately affects the health of people living in port communities by causing high levels of localized pollution. At the Port of Los Angeles, for instance, which is the busiest container port in the Western Hemisphere (it handles roughly 40% of U.S. imports), ships now surpass trucks, rail, and cars in emissions of nitrous oxide and particulate matter to portside communities. Populations surrounding the L.A. port have the region’s highest cancer risk from air pollution, and they have higher rates of asthma compared with the rest of the state.

That’s why we’re particularly excited about a green-corridor initiative involving Shanghai and Los Angeles, one of the world’s busiest container shipping routes. The cities’ ports announced a partnership facilitated by C40 Cities in early 2022, with a pledge to reduce emissions from the movement of cargo throughout the 2020s. They will also begin transitioning to zero-carbon-fueled ships by 2030.

The project evolved thanks in part to a campaign called Ports for People, spearheaded by Pacific Environment and communities in port hubs pressuring their local and state governments to address the environmental problems posed by their facilities. The coalition was instrumental in pushing the state of California to pass a zero-emissions ferry mandate, which in turn led South Korea, Japan, and Singapore to announce similar rules. In California alone, the move is expected to reduce the cancer risk for 20 million people and to save the state millions of dollars in public health expenditures. Advocacy by grassroots partners also helped force the state to approve a rule ordering ships calling on its ports to switch to low-sulfur fuels and requiring most of those docking at its largest ports to connect to shore power. The rule also required cleaner engine upgrades for its tugboats and other harbor vessels. Since then, the L.A. and Long Beach ports have spent hundreds of millions of dollars building the electrical infrastructure.

Pacific Environment was also involved in the 2021 launch of the Ship It Zero campaign, calling on retailers such as Target, Walmart, IKEA, and Amazon to transport their products only with carriers “taking immediate steps to end emissions” and to sign contracts promising to begin shipping their goods on the world’s first zero-emissions ships. As with coZEV’s, the group’s outreach has helped to prod the big retailers toward bolder carbon-related commitments. Among its more dramatic actions was an eight-minute “die-in” held last spring at a Long Beach Target (the chain imports 98% of its goods through L.A. and Long Beach) to highlight the eight-year discrepancy in life expectancy between port communities and the general public. Through their combined efforts, they are continuing to shift perceptions — in the industry and beyond — as to the sort of systems-wide transformation that might be possible.

A campaign called Say No to LNG aims to remind shippers, retailers, and the public that liquified natural gas, despite its greenwashed image, does not qualify as a cleaner “bridge fuel.” The methane-heavy substance is in fact a devastatingly heavy polluter, and it should have no place in green corridors or anywhere else in a sustainable shipping future. Shippers who retrofit their vessels to accommodate such an obviously not-long-for-this-industry option are setting themselves up to lose billions in stranded assets.

Groups in China, home to the world’s biggest ports, greatest shipping volumes, and leading shipbuilders, are working on an energy-efficiency design index to develop standards for domestic vessels in the country and are helping to establish green corridors within Asia. Our research partners also have begun ranking Asian ports on the various technologies they’ve adopted — whether shore-power infrastructure or electric forklifts — and making those assessments public as a way to inform citizens and pressure local officials to raise their climate-related commitments. Local officials, in turn, can lean on port operators and shipbuilders to better address the emissions and other pollutants resulting from their operations.

Partner organizations in the European Union are helping to advance the bloc’s already ambitious climate goals. They were instrumental in pushing the European Union to pass a recent law adding shipping to its Emissions Trading System. Ships must now pay a per-ton carbon tax on all greenhouse gas emissions generated by intra-EU voyages and on half the distance from extra-EU voyages, as well as on emissions resulting from berths in EU ports. A second law will require ships to begin switching to low-carbon fuels starting in 2025. Our partners at Transport & Environment, based in Brussels, are working to create a legal framework around green corridors in the region and to ensure that any claimed emissions reduction can be transparently monitored and, at a later stage, enforced.

At Opportunity Green, based in London, and Seas at Risk, in Brussels, our partners are focused on using legal avenues to enable national governments beyond the European Union to be more proactive about cleaning up their maritime-shipping industries. They are pushing for a global carbon levy on shipping and a just and equitable transition for the sector. They argue, for instance, that money raised through a levy scheme should go toward loss and damages suffered by countries in the Global South and that the shipping industry of the future must support decent jobs and improved health outcomes in all countries involved. This means, among other things, helping countries like South Africa and Morocco, which are poised to benefit from a greener shipping sector, avoid the “resource curse” that too often plagues communities living at the source of global commodities.

None of these multi-pronged negotiations will be easy, as our partners at Germany’s Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union (NABU) can well attest. A few years ago, NABU commissioned an assessment of two emissions-control areas that had been established in the Baltic and North Seas, in an effort to address the excuses routinely trotted out by the industry as a way to resist making change — for example, that it would be impossible to make their ships run on lower-sulfur fuels, or that extensive overhauls would bring bankruptcy. However, excuses related to a lack of money ring particularly hollow in light of the massive profits racked up by the industry over the months of Covid bottlenecks. The results showed that the reverse was true: shipping companies that had adopted cleaner fuels saw increased profits, and, as a bonus, the port communities involved saw major declines in local air pollution.

Armed with that evidence, NABU turned its attention to the Mediterranean, focusing on the region’s very visible cruise industry. Over the course of two years, campaigners liaised with relevant industry groups in Greece, France, Israel, Turkey, and beyond while collaborating with environmental groups already active in busy ports like Venice and Barcelona. Traveling to cruise ports all along the north shore of the Mediterranean, NABU staffers worked with scientists to measure air pollutants and then held press conferences to share their results. Widespread coverage in the press helped push local and national governments to address the pollution related to their cruise industries and shipping in the region generally. Though it entailed winning support from countries all around the Mediterranean — not to mention navigating the tense politics between Turkey and Israel and the diplomatic fallout of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — NABU ultimately helped convince them to submit a proposal to the IMO forcing ships in the region to use marine diesel rather than high sulfur fuels. They now have their sights on helping to establish an emissions-control area running from Norway and Iceland down to Spain and Portugal, an endeavor that, given the limited number of countries involved, should prove far less daunting.

Last November, the Northwest Seaport Alliance, a partnership between the Ports of Tacoma and Seattle, announced scoping plans for a green corridor with the Port of Busan in South Korea. Los Angeles and Long Beach recently established a partnership with Singapore to put in place a corridor focused on low- and zero-carbon fuels for bunkering, as well as on digital tools to support zero-carbon ships. An Australia–East Asia Iron Ore Green Corridor is in the works, and the U.S. Departments of Transportation and State have teamed with Transport Canada to establish a green corridor for the Great Lakes region. Last year at COP27 in Egypt, some of our partners launched the Green Shipping Corridor Hub, an online platform aimed at supporting the further deployment of green corridors around the globe.

Recently, Jesse Fahnestock, a project director at the Global Maritime Forum, based in Copenhagen, marveled over the momentum that we’ve seen in just the last 24 months. In addition to the establishment of so many green corridors, industry groups and national governments have signed a range of declarations and ambition statements related to finance, freight, and infrastructure. Jesse recalled how in March 2022, he and a few colleagues had traveled to Spain at the request of the U.K. government to speak to a group of industry representatives about the green corridor concept. They’d presented their ideas before an audience of 50 or so and were met by nothing but blank stares. Last month, after a year of continued engagement with port operators, cargo companies, local officials, and others, Jesse and his colleagues returned to Spain. While attending a session in Bilbao, they looked on in astonishment as an industry consortium formed right there on the spot, with participants agreeing to take on exactly the sorts of commitments that he and his team had floated to deaf ears one year earlier.

In July, the IMO is set to announce a new range of decarbonization goals, which presents an opportunity for the organization to align its ambitions with those of the Paris Agreement and to clarify the milestones it intends to hit in order to do so. In the meantime, green corridors will continue to provide the industry with a way to move forward in an arena that can otherwise feel unmoveable. The concept has given people across the industry as well as in government a sense that they can do constructive things now, without having to wait for the IMO or the global rollout of new fuels and vessels.

Back in 2021, the Dutch company trying to wriggle the visible-from-space Ever Given free from its perch in the Suez compared the vessel to a “beached whale” — an apt image for an industry long stuck in its polluting, law-flouting ways. After six days, though, a team of salvagers relying on a combination of tugboats, large-capacity dredgers, and high tides managed to finally push, pull, and dig the behemoth from its predicament. Overhauling an industry as massive as global shipping might feel like an equally Sisyphean task, but I’m confident that given the same sort of all-hands-on-deck approach we witnessed in Egypt, we’ll be looking at a carbon-free sector sooner than anyone might imagine. ◊