Before the U.N. General Assembly on September 22, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that his country aims “to have CO2 emissions peak before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.” The implications of this commitment are still being worked out and there remain many unanswered questions on how this new target will be achieved, but for now we celebrate this most welcomed announcement, one of the largest — in terms of emissions reductions — in history.

Peaking before 2030 raised no eyebrows, but net-zero by 2060 dropped many jaws

China’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), the pledge Beijing put forth as part of the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 2°C or less by the end of the century, sought to peak emissions around 2030. Unlike the latest announcement of carbon neutrality by 2060, the original NDC pledge had been repeatedly discussed and requested by international and domestic analysts before the 2015 Paris meeting.

As the largest emitter in the world, China produces roughly a quarter of global annual greenhouse gas emissions, more than the U.S. and EU combined, meaning that it has an outsized role in determining future temperature outcomes. Curious minds therefore examine China’s various policy plans and commitments in search of insights, generating a litany of unanswered questions, analysis, and commentary on the potential shape of China’s emissions pathway.

One clear theme that has emerged since the 2015 NDC announcement: peaking around 2030 was a relatively weak target as a peak in emissions will likely arrive early. Assessments of China’s peak emissions lead many to declare that they are likely to arrive earlier, given China’s recent trend of decelerating the pace of emissions growth. This recent announcement, that emissions will indeed peak before 2030, therefore, complies with what many analysts already assumed in their projections. More importantly, the 2060 target demystifies what an emissions pathway beyond 2030 might look like. This had been a major source of uncertainty as analysts debated whether emissions would peak and decline, or just plateau. This new announcement removes much of the uncertainty around China’s 2015 NDC.

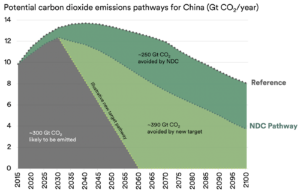

Peaking in 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality in 2060 requires a swift decline in emissions after peaking, meaning that the height of the peak defines the scale of the challenge. If China peaks around 12 Gt CO2, this implies a reduction of around 400 MtCO2 per year starting in 2030 in order to reach net-zero by 2060. This means that China would reduce emissions larger than those from the state of California every year between 2030 and 2060. That is why the new pledge is so crucial and surprised many, even those close to the climate policy circle in China. We demonstrate how much of an impact this might have in the figure below. To reach carbon neutrality by 2060 implies a cumulative emissions reduction of nearly 400 Gt CO2 between now and 2100 on top of reductions assumed under those pledged in China’s previous NDC.

2060 carbon neutrality has a large impact, but it comes with a litany of questions

If implemented with supporting policies and actions, a pathway to zero for the world’s largest emitter has large ramifications on temperature outcomes. Already, the Climate Action Tracker has calculated this alone could reduce projections on global temperature rise from previous estimates by around 0.2-0.3° C. This is not enough on its own to signal that global pledges add up to achieve a 2° C target, but it may help place the world within striking distance of 2° C and place 1.5° C within the realm of possibility. Further, as China joins the ranks of others with net-zero targets, it might just be a big enough signal for others to join in the race to zero.

That said, there remain many unanswered questions. Let’s start with the larger ramifications for long-term temperature outcomes. What happens after the 2060 target? As the figure suggests, China might still emit around 300 Gt CO2 between now and 2060. The IPCC Special Report on 1.5° C of warming shows that the world has a remaining carbon budget of 420-580 Gt CO2 between 2018-2100 (with the lower end having a high probability of limiting warming to 1.5° C and the higher end having a 50% chance, though there remains a debate on the exact range). This means that between now and 2060, even with this new target, China alone might emit around half to three-fourths of the remaining global budget, unless gigaton-scale, net-negative emissions are achieved beyond 2060. This means that near-term policy choices and the resulting investment decisions are of paramount importance.

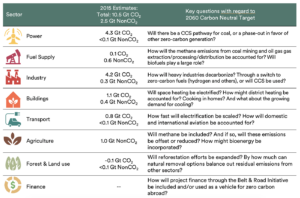

One of the timeliest questions, therefore, relates to China’s upcoming 14th Five-Year Plan (FYP) and how it might take critical steps toward achieving this target. The upcoming 14th FYP, expected to be released in March 2021, is a master plan for China’s economic and social development, drafted through intensive and multi-ministerial consultation with bounding targets that direct national policy and resources toward strategic goals for the next five years. Key sectors will all have to draft their own development plans in alignment with the upcoming FYP as well as the respective goals for 2030 and 2060. Expectations vary in terms of the changes needed in different areas of the economy.

The power sector, for example, has clear and well-developed low-carbon alternatives, and the share of generation from renewable sources such as wind and solar is expected to grow by fivefold to eightfold, together with advanced storage options that allow for greater system balance. Despite this potentially large growth in renewables, they are nowhere near enough to replace the massive fleet of coal-fired power plants currently operating in China. As the largest-emitting sector, the choices for this sector in the next FYP will be watched closely, as what scales up in China will have influence beyond its borders.

In transport, full electrification of passenger vehicles either through battery or hydrogen fuel cell technology will be the minimum requirement for the sector to reach net-zero emissions by 2060, and hopefully long-haul and heavy-duty freight follow suit. Questions remain for aviation and marine shipping whose emissions growth is the fastest, but the most difficult to mitigate.

China’s industrial emissions are especially important in a long-term zero-carbon pathway. Current emissions from industry are larger than economy-wide emissions from the entire European Union. Like transportation, most industrial emissions could be reduced through energy efficiency improvement; low-carbon fuel switching, including electrification; and alternative materials. And yet, heavy industries that are crucial to everyday life are still lacking mitigation options or alternatives, such as steel, cement, and petrochemical production.

In buildings, space heating and cooling present another area with huge untapped mitigation potential. Given the long lifespans of appliances and the buildings themselves, the next decade will be crucial to avoid lock-in of emission-intensive practices in the built environment.

Finally, decisions on finance and investments in each of these sectors are front and center in fulfilling the carbon neutrality pledge. According to research by Tsinghua University, China needs to invest $500 billion every year for the next 30 years to materialize the transition. We highlight in the table below key sectoral questions that will need to be grappled with. And while we point these out with China in mind, these are generalizable to other geographies seeking net-zero and below-zero targets. China’s balance sheet might be the largest, but balancing sinks with produced residual emissions from the very hard-to-decarbonize sectors will require careful consideration no matter the locale.

If China’s target ultimately includes other types of greenhouse gases aside from CO2, the task becomes more arduous but more beneficial to the climate. China produces annually around 2.5 Gt of CO2-equivalent emissions of non-CO2 greenhouse gases that will have to be either mitigated or offset to reach a truer net-zero target. China is yet to release a comprehensive non-CO2 mitigation strategy. Research has shown that China’s largest mitigation potential in this area comes from the industrial processes of producing fluorinated gas (F-gas) refrigerants and methane from the agricultural and coal mining sectors. China is already phasing down the production of F-gases and replacing refrigerants with less polluting ones through the country’s new National Green Cooling Action Plan. However, a quick transition to zero-emission cooling is needed for carbon neutrality, and as the manufacturer of 70% of the world’s cooling products, this shift in China will have enormous positive spillover effects across the world. This means that some solutions are already being explored but more is needed to address all non-CO2 sources.

Finally, and not to be overlooked, is the importance of land-use sectors and the potential for natural and technological carbon dioxide removal (CDR) options. Residual emissions — those that need to be balanced out by negative emissions solutions — from the agriculture, industry, and transport sectors in 2060 are estimated to be around 1 Gt CO2 and will still have to be offset by a combination of measures including CDR. Both natural and technological efforts will need to be scaled for China to move toward net-zero and ultimately net-negative emissions. China already made commitments in natural CDR and has made good progress. However, a quick upscaling of both natural and technical CDR options is necessary for balancing residual emissions along the pathway to zero and beyond.

Philanthropy can galvanize the field and carry this momentum forward

There is no doubt that China’s pledge is a hugely positive development despite the litany of questions that remain unanswered. More clues will no doubt be found in China’s mid-century strategy for deep decarbonization that is to be submitted to the UNFCCC by end of this year and in the 14th FYP next March. The climate philanthropy community has a long and successful history of engagement with China and is well placed to carry the current momentum forward.

Philanthropy can help detail the strategy and roadmap to reach this ambitious target in a just and sustainable way, while coupling these strategies with economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic. As an international community we also need to build on this momentum to galvanize support for deeper reductions in other geographies. With both the EU and China announcing their carbon neutrality goals, the U.S. now faces a critical moment with the world eagerly watching what comes next. As the largest emitter in the planet, China is not only taking a bold challenge by seeking carbon neutrality, but also embracing an international race to zero that will reshape the worlds’ technological and societal landscape.