We must dramatically reduce super pollutant emissions alongside carbon dioxide to achieve climate protection in line with the Paris goals.

The Paris Agreement says we should aim for global warming of “well-below 2 degrees,” and the IPCC special report on 1.5 degrees made that the standard to aim for. That’s such a tough goal on its own that it may not be obvious that there are options for the pathway to getting there – but differences in approach could mean millions of lives lost, or saved, between now and 2050.

In particular there is a choice about how to address short-lived climate pollutants, also called SLCPs or super pollutants. These substances, including black carbon, fluorocarbons and methane, are extremely potent, but have a short residence time in the atmosphere, and the fixes and alternatives are in most cases readily available. This means there’s a quick temperature response when cutting them; in the past this has been interpreted as meaning that whenever we get around to cutting them is fine, because there’s an immediate reaction.

However, that interpretation is based on two fallacies – first, climate policy has long ignored air pollution, and since super pollutants are also air pollutants or precursors to them, delaying cuts means putting up with more deadly pollution. Second, any warming we have to put up with is potentially dangerous – 1.5 degrees isn’t simply an end point where the pathway doesn’t matter – we want to cool down as soon as possible.

ClimateWorks has been trying to find a good way to communicate this point on the pathway, and then suddenly one was on front pages everywhere – flattening the curve of the coronavirus pandemic. The similarities are remarkably strong.

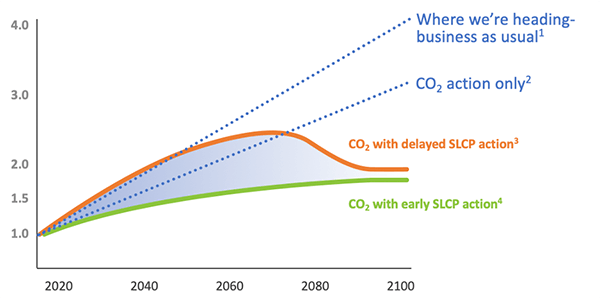

In the graphic below you can see the difference between taking action on CO2 emissions but waiting to deal with super pollutants, versus acting on them today – the latter flattens the curve, with all that implies. There is still warming, but it is smoother and levels off without a big early spike and overshoot of sustainable levels. According to a leading expert on this issue, Professor Drew Shindell, unless we reduce short-lived climate pollutants quickly, millions of people will suffer or die early from poor air quality, and will struggle to maintain food security against crop yield losses – consequences contained in the gap between the two curves.

Analysis shows that aggressive mitigation of super pollutants alongside CO2 will result in seven times the temperature impact by 2050 compared to working on CO2 alone – indeed, 87% of the reduction in temperatures that we can achieve by 2050 will be due to cutting SLCPs.

Analysis shows that aggressive mitigation of super pollutants alongside CO2 will result in seven times the temperature impact by 2050 compared to working on CO2 alone – indeed, 87% of the reduction in temperatures that we can achieve by 2050 will be due to cutting SLCPs.

Aiming at super pollutants also makes it easier to connect with policymakers and the public. It’s difficult to reach most people around the world about our agenda of meeting the Paris climate goals if we talk in terms of arcane global agreements, complicated science, or solutions that are out of reach for them.

However, air pollution is something that everybody understands – you can see it, and you can feel it in your lungs. Pollution is also a major preoccupation of governments – indeed a much higher one than climate in most parts of the world. By linking air pollution, health and greenhouse gases via super pollutants, we can enter a dialogue with countries and regions that are putting their development and health priorities first. Tackling super pollutant emissions will help improve health, agricultural yields, and economic progress.

We must dramatically reduce super pollutant emissions alongside CO2 to achieve climate protection in line with the Paris goals. Tackling SLCPs immediately will protect millions of people from harmful air pollution, and it will avoid temperature overshoot and the associated impacts on humans and the environment. It’s time we took fast action.