Climate philanthropy is in a unique position to accelerate progress on carbon removal and increase the odds that multiple removal approaches reach gigaton scale before 2050.

With the landmark publication of the IPCC’s Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5° C, the science is in and the conclusions are clear: by 2050, both the rapid and deep decarbonization of the global economy and the large-scale deployment of carbon removal approaches are imperative for meeting climate goals. And while emissions reductions have long been front and center of the climate conversation, last year saw a shift in the conversation that aimed to add substance to the second half of the climate equation. A plethora of reports (The National Academy of Sciences, New Carbon Economy Innovation Plan, and the Royal Society Report to name a few) put pen to paper on the critical need for and “state of” many of the leading carbon removal solutions. With enough information in hand, we are now well equipped to move past debating ‘why carbon removal’ to ask ‘how can we achieve carbon removal at scale before midcentury?’ Thus, it is of critical importance to take stock of what we know (and don’t) about carbon removal solutions, and to develop an associated philanthropic strategy that will make it possible to realize the full potential and scale of these solutions, while taking into account their varying levels of technological readiness.

What is Carbon Removal at Scale, and How Can We Achieve It?

Scientists estimate that carbon will need to be removed at the scale of over 10 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2050 — an amount that roughly equates to a quarter of total global annual emissions today. In order to reach such a monumental scale by midcentury, work needs to begin today on researching and deploying a portfolio of carbon removal solutions, with an interim goal of removing 6 gigatons of CO2 per year by 2030. Constituting less than two percent of all philanthropy, we don’t imagine climate grants alone will get us to scale but we can help create better rules and tools to attract the patient capital and private investment needed to get the job done.

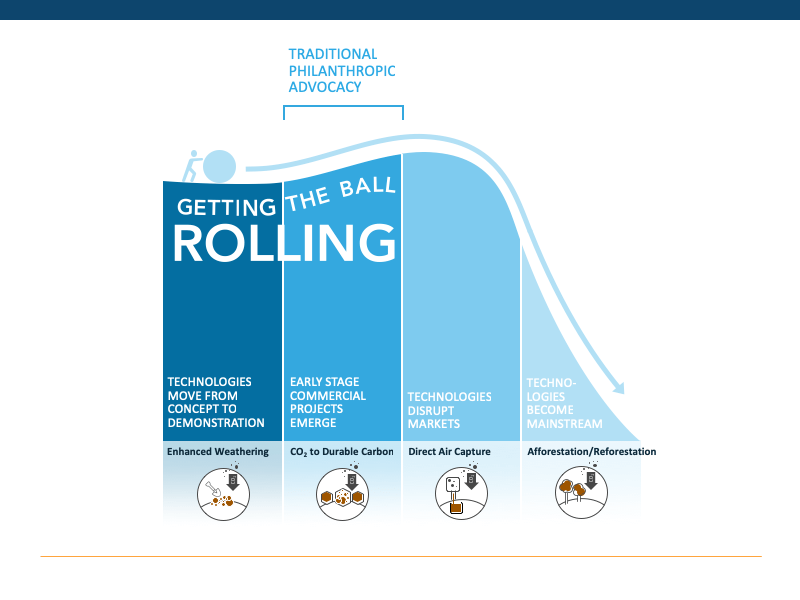

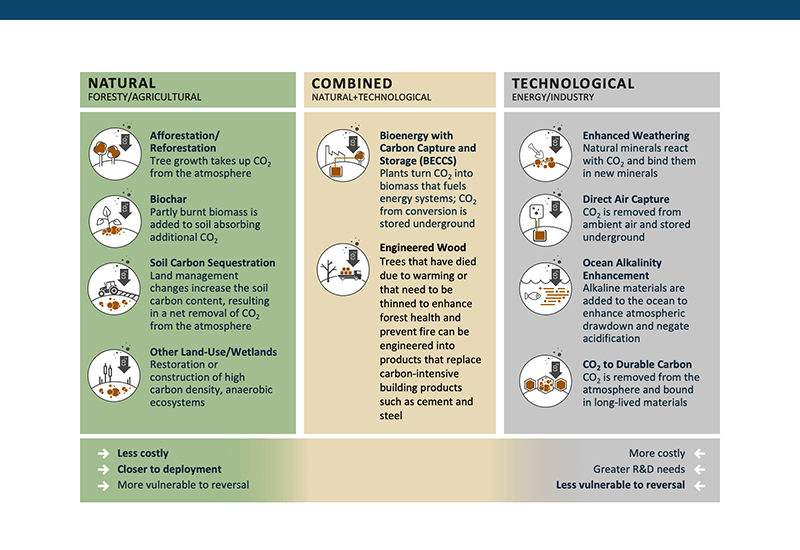

And while this task is daunting, philanthropies have decades of experience engaging with governments, the private sector, and nonprofits in support of innovation and the deployment of new climate solutions; solar is a notable example. Today, each carbon dioxide removal approach sits on the innovation curve at different levels of technological readiness. Many solutions, like direct air capture (DAC), forestry, and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) are ready for traditional philanthropic support that funds policy development, advocacy, and communications.

Other solutions, however, still need significant investments in fundamental research, evaluation of challenges and opportunities, and early demonstrations. Some foundations fund such early-stage solutions in the realm of peer-reviewed scientific papers, but others fund advocates to champion new policies to help scale solutions. Because it is too early to know which solutions will prove to be the most scalable or economical, it will be essential to exercise humility in acknowledging that we don’t know which approaches will play the largest role in climate mitigation until these techniques are proven in real-world implementations. The urgency and scale of the climate crisis necessitate that we leave no option unexamined, no stone unturned.

Getting More Solutions Ready for Scale

Moving outside of our funding comfort zone will be critical to reaching scale with a portfolio of carbon removal solutions. Not only do we need to get the ball rolling by creating an enabling environment for mature solutions, but we need to do technology and policy assessment for early-stage options to understand their ability to contribute to negative emissions at scale.

To be clear, we are not suggesting that more mature solutions merit less support—rather, forestry, BECCS, and DAC simply require different types of support concomitant with their relative level of technological readiness. For instance, funding for communications is required to socialize the understanding that not all removal equates to BECCS, and that direct air capture is poised for rapid cost reductions as it will benefit from learning by doing and economies of scale (much in the same way as solar photovoltaics continually beat expert forecasts on price declines and capacity additions). However, we will focus this discussion on several less-heralded carbon removal solutions: enhanced weathering, soil carbon sequestration, and ocean removal approaches. Many of these solutions still have major question marks that philanthropic funding can help answer in order to drive their development forward.

Enhanced weathering: Over geologic time scales, the natural weathering of rocks containing certain minerals — like serpentine, silicates, carbonates, and oxides — draws down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and stores it in stable mineral forms, thereby playing an important role in regulating atmospheric CO2 concentrations. The centuries and millennia that these reactions typically take are too slow to help with the climate crisis. Fortunately, there are ways of safely speeding up the weathering. By grinding up rocks to increase their reactive surface area or by adding heat or acids to speed up reaction rates, enhanced weathering could be an important climate solution with huge potential to scale. (Experts estimate that, after considering energy requirements, enhanced weathering could reasonably remove up to 4 gigatons of carbon per year.) Philanthropy can support basic research to substantiate these claims in the real world, focusing on supporting process improvements and mapping resource potentials. If the benefits of enhanced weathering prove to exceed the challenges, the near-term research efforts funded by philanthropy can help unlock greater government RD&D and help secure private capital to move this approach from the lab to pilots.

Soil carbon sequestration: Soils have the potential to store carbon at scale, though global soils have historically lost an estimated 133 Gt of carbon due to human-driven land use change. Today, there are a wide variety of land management strategies, practices, and technologies that fall under the aegis of soil carbon sequestration that can restore a portion of this lost carbon. However, there is no one-size fits all system that can help realize that scale. The efficacy of these practices turns on local soil type, climatic factors, and crop type. Philanthropy has been and should continue to fund research to better answer basic questions around which practices are most effective in what scenarios and how permanent the removal is. In addition to practice change, research to explore new varieties and crop types that sequester more carbon will be critical. For example, we are learning that switching to crop types with long roots, such as kernza, may support even greater soil carbon storage potential than can be realized through land management practice changes alone.

There is also currently no streamlined, consistent, and cost-effective way to measure and verify soil carbon sequestration on the farm-level. This lack of protocols could greatly influence our assessment of soil carbon sequestration potential and hinder the incorporation of these practices into climate policy frameworks. Philanthropy can play a big role in incentivizing streamlining among current standards and in helping to set up the frameworks of the future.

Sequestration efforts should also be combined with efforts to boost crop yields, allowing us to both store more carbon in the soil, prepare our food systems for the effects of a changing climate, and free up additional land for high-carbon ecosystems (such as forests and wetlands). Increasingly, land will be stretched to deliver on multiple priorities — from food production to ecosystem services to bioenergy production to carbon sequestration — and philanthropy can play an important coordination and consolidation role among these veins of research.

Ocean approaches: There are a number of ocean-based approaches that haven’t been explored in detail to-date. In fact, the National Academy of Sciences excluded ocean approaches (except coastal wetland restoration) in their recent landmark report. These approaches utilize ocean ecosystems to sequester carbon and can include direct ocean capture, kelp farming, ocean alkalinity enhancement, and other blue carbon approaches. Because many of these strategies are in the early stages of development today, it will be important for philanthropy to support analyses to better understand the technical and economic potential for these solutions, as well as any risks from early deployment that would necessitate governance standards in the near term.

Climate philanthropy is in a unique position to accelerate progress on carbon removal and increase the odds that multiple removal approaches reach gigaton scale before 2050. Our theory of change is rooted in our abilities and limitations. Philanthropy can support research (both into technical aspects and communications and messaging strategies), fund advocacy, policy development, and governance frameworks, and take on risks that governments or the private sector can’t or won’t. However, philanthropic resources are small relative to the many trillions in public and private capital that will ultimately need to be allocated toward climate solutions. Thus, any credible strategy from philanthropy should be focused on removing barriers and unlocking other forms of capital.

The task ahead is daunting, and we are clear-eyed about what Paris-compatibility will entail – multiple simultaneous transformations in the ways that we produce, transport, and consume. Carbon removal is not a stand-alone task, but must be integrated into the larger economic and ecological systems they are deployed into. There are some carbon removal approaches that we know will have multiple benefits and can scale — these we should begin supporting through communications, policy development, advocacy, and investment. There are also many other approaches where it is too early to tell if they will be able to contribute to large-scale removal — but the urgency of the problem demands that we explore all options that hold the promise of arresting and reversing the climate crisis.

For further reading: Our 2018 blog post, ‘Carbon Dioxide Removal is a Necessary Complement to Deep Decarbonization’, makes the case for including carbon removal as an integral component of the global response to the climate crisis.