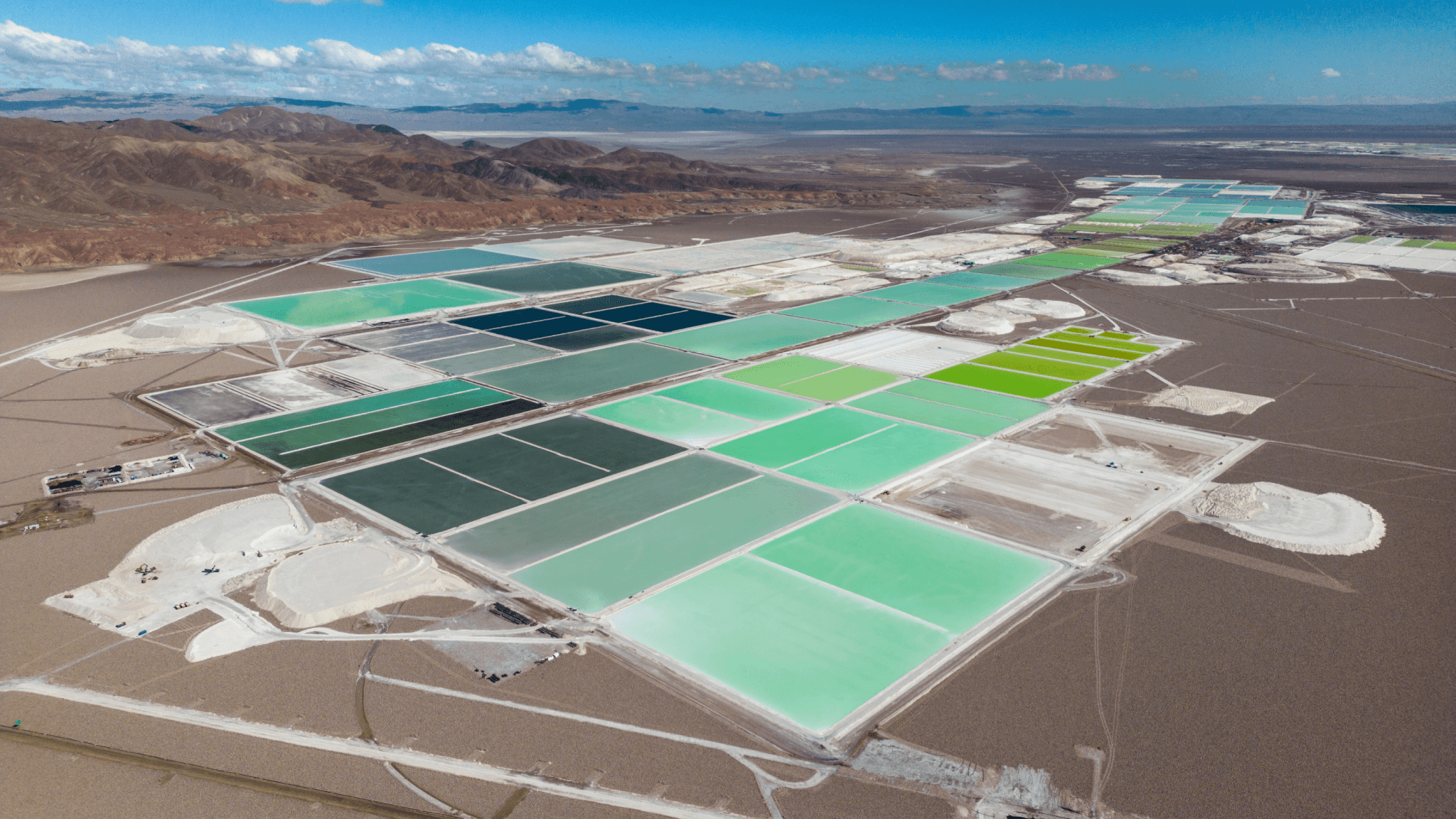

Electric transportation of all kinds helps mitigate climate change, reduce air pollution, and improve health outcomes — and offers a key opportunity to help end global dependency on oil. However, until a truly circular design is viable, producing any vehicle relies on materials such as steel, oil, and a number of minerals. Electric vehicles already drastically reduce the volume of raw materials needed to power our transportation system. Still, there is a growing recognition that getting to 100% electrified transportation will require an expanded supply of critical minerals.

Recycling can provide between 25% and 55% of the expected growth in minerals needed for electric vehicle batteries, and additional minerals must be extracted with the lowest possible impact on communities and the environment. In our previous blog post, we shed light on the impacts of mining for critical minerals and the priorities for policies to improve the battery supply chain. Currently, the European Union, China, India, and the United States are taking steps to review their domestic slice of the global battery supply chain and draft responsive regulations that address mining for critical minerals, battery manufacturing, and its end-of-life practices.

One voluntary standard is emerging as an important tool in service of both industry and policy ambitions for improving mining impacts. The Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) provides a template for model regulations on mining practices and is making strides to support automakers and battery manufacturers in leveraging their growing demand for minerals to incentivize necessary change in mining.

A singular mining standard that considers responsibility from multiple perspectives

The IRMA Standard for Responsible Mining is a one-of-a-kind standard that measures global mine sites against a set of best practices developed over a decade through multi-stakeholder dialogue. IRMA is the only standard for large-scale mining that is governed equally by NGOs, labor unions, mining-affected communities working alongside mining companies, the finance sector, and companies who purchase mined materials for the products they make (e.g. vehicles, jewelry, electronics, wind turbines, etc.). It offers both expertise and a pathway for transforming the mining sector. As a voluntary initiative, it will never replace the essential need for laws and regulations that would bind all companies. But governments and citizen advocates can use IRMA’s 15 years of work to help define best practices for protecting human rights, clean water, biodiversity, Indigenous rights, worker rights, and economic opportunities after a mine closes.

More than a decade of work went into developing the standard, including global public comment periods for the first draft in 2014 and the second draft in 2016. Cross-stakeholder working groups weighed in on controversial issues, and the draft standard underwent field tests at mines in the United States and Zimbabwe. The final standard integrated all that feedback and is now available for auditing, with 26 chapters built around four main principles: social responsibility, environmental responsibility, business integrity, and planning for positive legacies.

As a tool for creating positive market pressure, IRMA offers an opportunity for automakers and component manufacturers to use the IRMA Standard and audits of mines as a tool in their due diligence to understand harm in the supply chain and to leverage improved practices. Already, consumer-facing brands are developing new purchasing contracts that ask suppliers to be audited against the IRMA Standard, share detailed information on performance, show improvement, and reach key achievement levels in a time-bound schedule. For example, in the automotive sector, BMW, Mercedes, Ford Motor, GM, Volkswagen, and Tesla have all joined IRMA.

IRMA is a key stakeholder in helping governments develop a regulatory pathway for improved mining practices. The initiative has been uniquely referenced in the Biden Administration’s report on sustainable supply chains, in critical minerals strategy by the European Parliament, and in a report supported by the Australian government evaluating which standards would make Australian materials most competitive in the European markets for battery materials. The latter identifies IRMA as a “no regrets approach” because of the comprehensive nature of the standard and IRMA’s multi-stakeholder base.

The IRMA standard makes it a key benchmark for indicators across a wide range of advocacy spaces. As we move to energy sources that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we must not exacerbate the impacts already in progress in a climate-stressed world. By connecting voices from different aspects of mining, IRMA’s coverage of diverse issues helps to ensure that we do not trade issues off one another. By measuring the impacts of mining operations against the full range of issues, we can have a fuller picture to support solutions that more holistically address a world responding to drought, flooding, and increased conflict.

Empowering philanthropic engagement

Philanthropic support for electrification can go hand-in-hand with supporting the field in advancing the sustainability of batteries. While we push to end tailpipe pollution that harms the climate and burdens communities, we can support the growing call to embed improved mineral sourcing practices, circularity, and even net-zero manufacturing into our vision of a clean transportation future. The global nature of the battery supply chain and the broad application of minerals that power the climate transition offers philanthropy an opportunity to deepen engagement.

We can amplify our impact at the ground level of the battery supply chain with a consistent and unified voice. For example, philanthropic partners and grantees alike can spotlight the IRMA Standard as a vector for corporate engagement and a template for government regulations. We need to signal externally that it is possible for automakers and battery manufacturers to be a force for improvement. Preventing greenwashing is also critical, which is why we need comprehensive best-practice standards that are accountable to NGOs, labor unions, Indigenous communities, and others directly impacted by mining. In turn, we can continue to build advocacy power toward binding regulations on mineral sourcing, battery recycling, and end-of-life practices.

Because this work touches so many lives and key issues, this is an opportunity for philanthropic collaboration across expertise and dedication to human rights, clean water, biodiversity and conservation, Indigenous stewardship, worker rights, heavy industry, climate mitigation, and more. In our next blog post, we will dive deeper into organizational approaches for working on transitional minerals and share our learning from working with philanthropic partners.