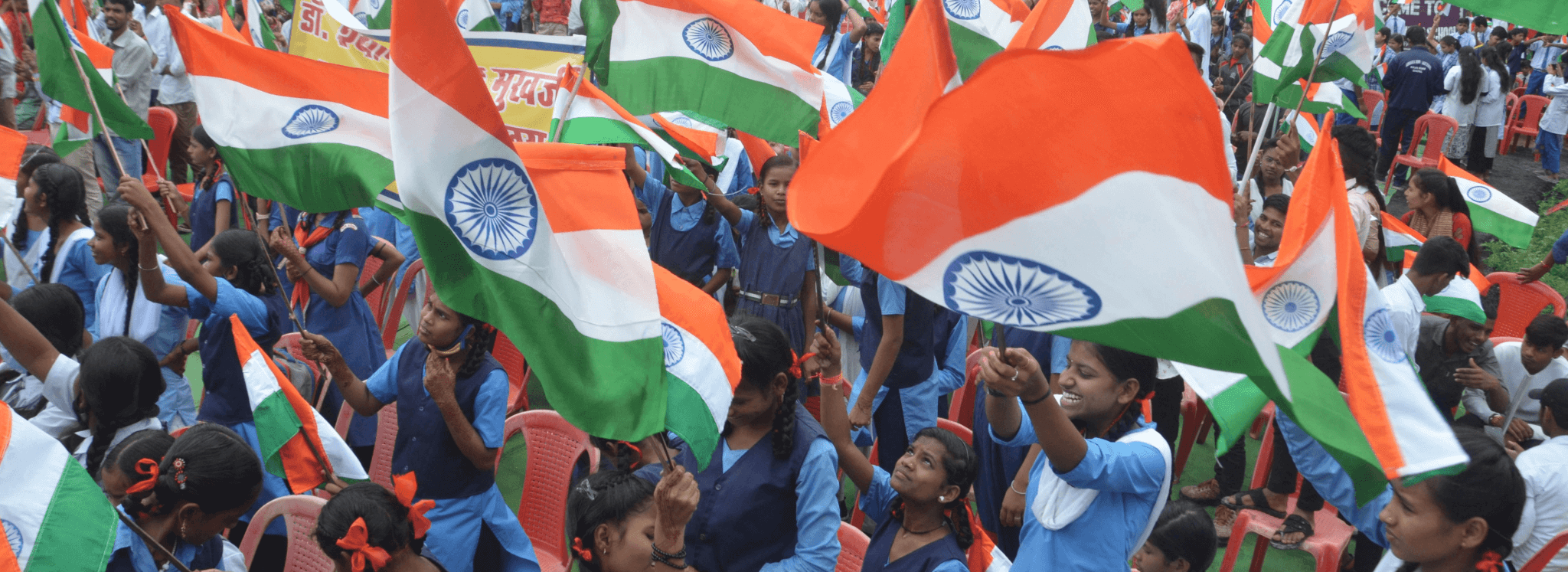

At the 2021 UN climate conference in Glasgow, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a lofty net-zero emissions target for India by 2070, significantly boosting the country’s climate profile in the lead-up to completing its landmark 75 years of independence dubbed India@75.

As part of the ambition, Prime Minister Modi committed to raising non-fossil-fuel-based energy capacity to 500GW, meeting 50% of energy requirements using renewables, reducing total projected carbon emissions by 1 billion tons, and decreasing the carbon intensity of the economy to less than 45% — all by 2030. India’s recently updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), a climate action plan that came out of the Paris Agreement, further cemented two of these goals by officially pledging to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 45% from the 2005 level and achieving 50% of cumulative electric power from non-fossil-fuel-based energy resources by 2030.

These climate actions have established India as one of the leading emerging markets to transition toward clean energy. This can be seen by the volume and pace of wind and solar construction, the rapid adoption of electric vehicles, a rapid expansion of renewables and battery manufacturing, and the country’s early-mover status on emerging clean technologies like green hydrogen.

While these energy transitions are key pillars of India’s efforts to mitigate adverse climate change impacts, an equally significant effort is the broader economic transformation that is underway. Spurred by shifting geopolitical fault lines and India’s own development imperatives, the country has elevated strengthening domestic manufacturing, creating local jobs, securing supply chains, and fortifying energy security as the cornerstones of its climate and clean energy actions. For India’s decarbonization journey to align with inclusive economic growth, the country must ramp up ongoing infrastructure reform and navigate the internal complexities of federal politics and land and labor systems, as well as the external challenges of securing low-cost transition finance.

With most recent estimates suggesting that India will need more than $17 trillion in investments to meet its net-zero goals, the moment for developed economies to come forward and support these efforts is overdue. Despite this shortfall, India is continuing to chart its own unique pathway that can provide learnings and templates for other emerging economies.

Transforming India’s energy and transportation sectors

India is among the world’s top five largest renewable energy producers and has received global recognition for its renewable energy deployment. In August 2021, India reached the commendable milestone of 100 GW of installed renewable energy capacity. Estimates show that India’s renewable energy sector grew at an annual rate of 17.5% between 2014 and 2019, during which the share of renewables in the country’s total energy mix increased from 6% to 10%. Thanks to favorable government policy, foreign direct investment in the renewable sector has risen steadily and amounted to a cumulative $10.81 billion between 2015 and 2022.

India’s ambitious targets and policy signals will continue to attract foreign and domestic investments in the sector and lay the groundwork for the country to emerge as a solar PV manufacturing hub. As a crucial step, the Production Linked Incentive funding scheme (PLI) introduced in 2021 incentivizes companies to set up solar module plants in India as well as electric vehicle or EV manufacturing. As manufacturing becomes increasingly cost-competitive, greater financial incentives and support could enable India to play a key role in diversifying supply chains. However, the country will have to bridge some challenges at the national and sub-national levels, including grid modernization and the improved financial health of utilities.

India is also rapidly moving towards transforming its mobility sector. By 2030, the government aims to have EV sales account for 30% of private cars, 70% of commercial vehicles, and 80% of two- and three-wheelers. In 2020, the central government announced the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (FAME India) to incentivize the adoption of EVs, extending the scheme until 2024.

In addition to R&D, subsidies, vehicle scrappage policies, and charging infrastructure, India also took big strategic steps toward developing a thriving domestic battery industry and creating a footing for Indian manufacturers in the global energy storage market. India launched the National Programme on Advanced Chemistry Cell Battery Storage with an outlay of $2.5 billion over five years, which can enable large-scale domestic battery manufacturing and serve the dual purpose of boosting renewable electricity generation and transport electrification.

There has also been significant subnational action, as nearly 20 states have recently finalized or notified EV policies. India will still need a cumulative investment of more than $180 billion this decade to meet 2030 goals and a stronger policy framework to resolve challenges related to upfront EV cost, battery sustainability, and infrastructure development. A concerted policy push will be key to bolstering a competitive EV ecosystem and capitalizing on benefits from targeting new frontiers like heavy-duty vehicles.

The road to 2030

As India looks ahead at the next 75 years, it can chart a development pathway that avoids locking in emissions-intensive infrastructure. This will require significant domestic and global resources and willpower. Key factors will include timely and adequate policy interventions, private sector led-innovation, and the rapid availability of low-cost capital. Drastic drops in the cost of solar and government schemes like KUSUM and Saubhagya, for example, have led to affordable and sustainable energy solutions for rural communities across the agrarian value chain.

The real challenge for India, however, lies in simultaneously bringing millions of people out of poverty. The impact of climate change in the country is also being felt more acutely in heat waves and other extreme weather phenomena. India’s prime objective has been to ensure its decarbonization journey is in step with achieving sustainable development goals.

Compared with other industrialized countries, India’s pace of deploying clean, affordable, and efficient energy systems will have to be much faster as it also seeks to guarantee access to energy and mobility, clean cooking fuel, food security, cooling, and disaster resilience.

What lies ahead is the difficult but imperative task of providing sustainable livelihoods, clean air, and a just and equitable transition to clean energy. Can India replicate, scale, and capitalize on its successes to showcase inclusive, low-carbon economic growth for developing countries? India is demonstrating leadership and emerging as a clean energy solutions provider. But the international community has a vital role to play in catalyzing this momentum and enabling India’s successful transition. The years leading up to 2030 will be crucial.