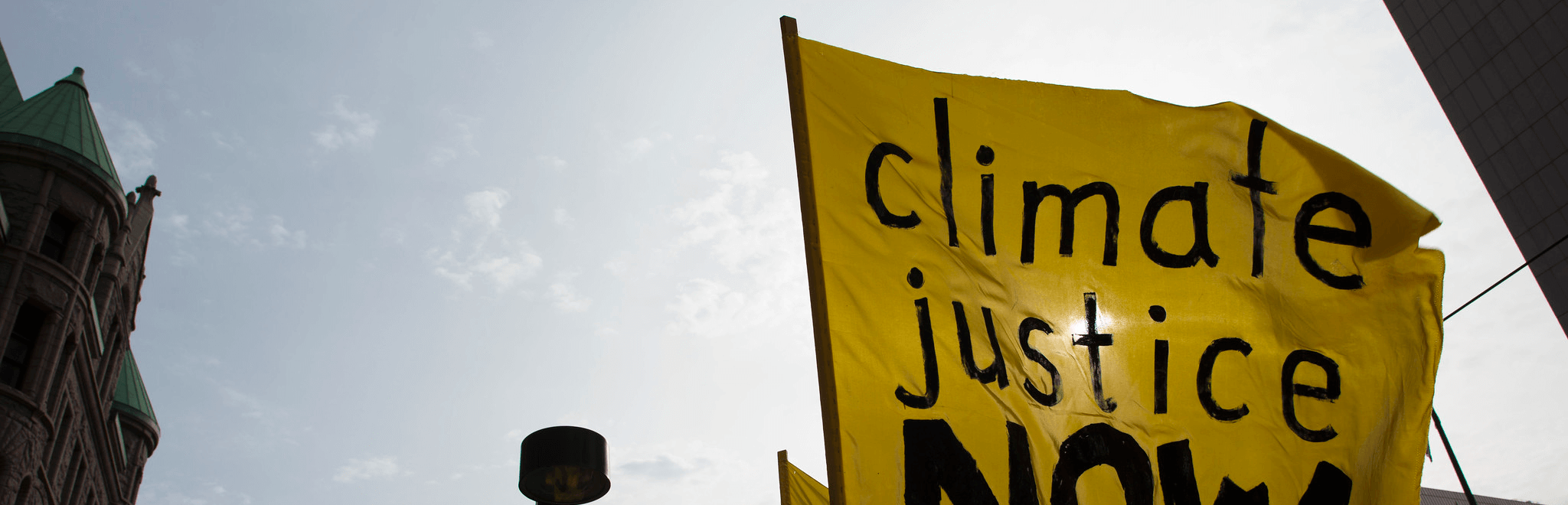

Three years ago, ClimateWorks kicked off its 2050 Today initiative to examine emerging strategies that are needed in order to meet the international goal of limiting global warming to well below 2°C. At the time, few of us within the predominantly white climate movement would have imagined that in 2020, ‘today’ would be defined by the global Covid-19 pandemic and a massive global outcry against systemic racism. We—the white-centric climate movement, myself included—are now seeing a ‘today’ that is profoundly different from the one we expected when the initiative came about, begging the question of why we failed to anticipate or address these major issues sooner, and how they should be reflected in the ongoing thinking that shape climate strategies.

Covid-19 and the racial justice movement have shown how much of the world’s population is vulnerable to climate change and how much more climate mitigation pathways need to account for these marginalized people. Last year, ClimateWorks looked closely at how our work extends beyond technological climate solutions and uplifts the world’s most vulnerable people by examining our strategic alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The assessment showed that pursuing climate mitigation strategies does support sustainable development in many cases, and confirmed a predominant view of the climate community that without drastic reductions of global emissions, many more people will face climate impacts. But how the benefits of mitigation strategies accrue in the short and medium term for people that are marginalized and climate-vulnerable, and most often Black, Indigenous, and People of many Colors (BIPOC), is something we continue to wrestle with.

While the initial 2050 Today exercise in 2017 highlighted priorities for mitigation in sectors such as industry, carbon dioxide removal, and finance, 2050 Today this year set out to explore intersectional themes driven by the amorphous power of people, interconnection, and imagination such as behavior and lifestyle change, civil mobilization, and equitable and just transitions. Following the global Covid-19 outbreak, ClimateWorks hosted several virtual 2050 Today meetings, including a dialogue with three esteemed science fiction writers, Kim Stanley Robinson, Chinelo Onwualu, and Brenda Cooper. The goal of the discussion was to stretch our imagination about what 2050 might look like and climate mitigation pathways that can help take us there.

The discussion profoundly illuminated the limitations of our thinking as it took place during the early month of June, at the height of the racial justice movement following the murder of George Floyd in the U.S. It elevated how much race can influence a person’s perspective due to the long history of whiteness and anti-Blackness in the U.S. and globally. But more importantly, it elevated two important take-aways as we try to reconcile the reality of Covid-19 and systemic racism with a climate-safe pathway to 2050.

The narrative is bound by storyteller’s conditioning and thus its assumptions must always be interrogated

The narrative of climate action and climate solutions is continuously shaped by decision-makers in positions of power and tirelessly elevated by people who have access to those decision-makers. The narrative of climate action and solutions is white-dominant and therefore limited to its single point-of-view and the largely white audience that stands to benefit from it. If this narrow narrative does not expand to include BIPOC voices and perspectives, then we run into the risk of perpetuating global inequality in the name of climate action. The issue is that oftentimes we don’t even realize that our conditioning both shapes and limits our worldview. For example, Onwualu highlighted that a white writer’s version of a climate dystopia looks a lot like a developing country, whereas BIPOC writers may imagine a climate-driven disruption as an opportunity to rewrite the current power structures and hierarchies. Therefore, we must engage in continuous interrogation of our assumptions around climate solutions and the ways we choose to pursue global climate goals. Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie makes a compelling argument for seeking to understand any one place or any possibility from a multitude of perspectives, saying that “if we reject a single story (to invite many stories instead)…we regain a kind of paradise.” For instance, if we interrogate the assumptions underlying our strategy for electrifying road transportation and invite BIPOC perspectives, our goals might remain the same, but the approaches might change and the immediate beneficiaries of the solutions might broaden.

Traditional approaches to decarbonization are still important, but not at the expense of marginalized communities

The mainstream and white-dominant climate action movement has been reinforcing an illusionary boundary between itself and the environmental justice movement, while making the voices of BIPOC communities fighting against the health impacts of climate change appear distant and irrelevant. The heightened global awareness of pervasive racial injustice has elevated the voices of Black climate activists that are pointing out the inherent racism of this artificial boundary. One critique of this phenomenon explains that some believe they have a “better chance convincing racists to support the climate movement than engaging minorities across the world.”

At the same time, BIPOC communities have the most to gain and lose in the climate fight. As Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson wrote in her op-ed in the Washington Post, “If we want to successfully address climate change, we need people of color. Not just because pursuing diversity is a good thing to do, and not even because diversity leads to better decision-making and more effective strategies, but because, black people are significantly more concerned about climate change than white people (57 percent vs. 49 percent), and Latinx people are even more concerned (70 percent).” Moreover, BIPOC are more likely to bear the health impacts from fossil fuel-induced air pollution, while recent studies have also shown that BIPOC are dying from Covid-19 at disproportionately higher rates in the U.S., relative to the white population. These important factors mean that ensuring a prosperous future for all requires us to understand the impacts of global climate change on marginalized communities, and bring their voices to the table, including people that live in coastal cities, informal settlements, drought-ridden areas, economically disadvantaged and underserved areas, and many others.

Guiding questions to shape 2050 strategies

The journey to calibrate and shape climate priorities for 2050 is a continuous effort. The Covid-19 pandemic and the re-energized racial justice movement have elevated the tensions in thinking about climate priorities in the near term and the future. As we continue to wrestle with how to shape our 2050 initiative and ongoing climate change mitigation work, three key questions should remain at the top of mind:

- How do we dismantle white dominance in the climate movement and address systemic racism in clean energy transition while lowering emissions?

How do we close the distance between the two priorities? - Where and how does long-term decarbonization enhance and/or suppress progress on Sustainable Development Goals?

What is protected and what is sacrificed in the energy transition? - Which incremental steps can we take to bring marginalized, climate-vulnerable BIPOC communities and voices to co-imagine deep decarbonization pathways toward 2050?

What stands between us and transformative action?

These difficult questions do not have a single answer but present an opportunity to seek many perspectives and views. Continued self-reflection, commitment, and honest effort can steer us in the right direction, starting today.

Photo credit: Fibonacci Blue